Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten@GJW:

DE

Statistik anwenden

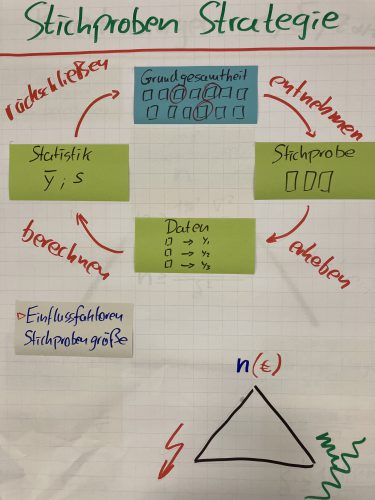

Die Hypothese soll auf ihre Gültigkeit in der Grundgesamtheit überprüft werden. Im Allgemeinen ist die Grundgesamtheit so umfangreich, dass ein Überprüfen in der vollständigen Grundgesamtheit zu aufwendig oder gar nicht realistisch wäre. Hier hilft die Statistik: Der Grundgesamtheit wird eine Stichprobe entnommen. In dieser Stichprobe werden die Daten erhoben, ausgewertet und die Gültigkeit der Hypothese geprüft. Dieses Ergebnis der Überprüfung wird auf die Grundgesamtheit zurückgeschlossen: Was in der Stichprobe gilt, gilt auch in der Grundgesamtheit (vgl. Bortz und Döring, 2006).

Drei Aspekte nehmen wesentlich auf die Größe der Stichprobe Einfluss: Der Aufwand, der investiert werden soll; die Ungenauigkeit, mit der eine ausreichende Aussagekraft des Ergebnisses erzielt wird; das Risiko, beim Rückschluss einen statistischen Fehler zu begehen. In diesem Spannungsfeld gilt es, die Balance zu finden: Mit vertretbarem Aufwand ein Ergebnis mit vertretbarer Ungenauigkeit zu finden, das mit einem vertretbaren Risiko des Irrtums auf die Grundgesamtheit zurückgeschlossen werden kann (vgl. Cohen, 1988; Siegel und Castellan, 1988).

Beispiel: Soll eine Hypothese überprüft werden, die besagt, dass mehr als die Hälfte für etwas sind, kann ein verhältnismäßig ungenaues Ergebnis toleriert werden, wenn die Verteilung 70% für 30% gegen wäre. Eine Ungenauigkeit von 10% wäre unbedenklich in der Ergebnisinterpretation. Liegt das Ergebnis hingegen nahe 50%, darf die Ungenauigkeit nicht zu groß sein, da sich das Ergebnis gegebenenfalls umkehren könnte (vgl. Bortz und Döring, 2006).

Eine übliche Konvention für ein vertretbares Risiko des Irrtums liegt bei 5% (vgl. Field, 2013).

EN

Applying Statistics

The hypothesis should be tested for its validity within the population. In general, the population is so large that testing the entire population would be too costly or even unrealistic. This is where statistics help: A sample is taken from the population. In this sample, data is collected, analyzed, and the validity of the hypothesis is tested. The result of this test is then generalized to the population: What holds true in the sample also holds true for the population (see Bortz and Döring, 2006).

Three aspects significantly influence the size of the sample: The effort to be invested; the inaccuracy with which sufficient reliability of the result is achieved; and the risk of making a statistical error when generalizing the result. In this context, it is important to find a balance: to obtain a result with acceptable inaccuracy at a reasonable cost, which can then be generalized to the population with an acceptable risk of error (see Cohen, 1988; Siegel and Castellan, 1988).

For example, if a hypothesis is to be tested that suggests more than half of the population supports something, a relatively inaccurate result could be tolerated if the distribution were 70% for and 30% against. An inaccuracy of 10% would be acceptable in interpreting the result. However, if the result is close to 50%, the inaccuracy cannot be too large, as the result might reverse (see Bortz and Döring, 2006).

A common convention for an acceptable risk of error is 5% (see Field, 2013).

Geplante/Erforderliche Verbesserungen

tbd